The unforgiving nature of live broadcasting, where a single dropped frame can disrupt an experience for millions, has long relied on a security model of physical isolation, but this approach has become dangerously obsolete in an interconnected, IP-driven world. While the corporate IT sector has embraced the “zero trust” framework—a model that assumes no user or device is inherently trustworthy—a direct application of its identity-centric enforcement would be catastrophic in a live production environment. The constant credential checks and agent-based monitoring common in enterprise settings would introduce crippling latency and jitter, threatening the very signal they are meant to protect. This reality has forced the broadcast industry to forge its own path, reinterpreting zero trust not as a rigid set of rules but as a dynamic, behavioral-based philosophy designed to operate silently and seamlessly in the background, ensuring the show always goes on.

The Inevitable Collision of IT Security and Broadcast Realities

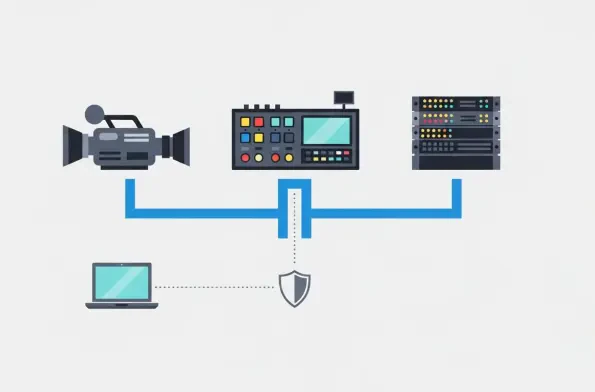

The fundamental incompatibility between traditional IT security and broadcast operations stems from the highly specialized nature of production hardware. Live environments are not populated with standard servers and workstations; instead, they are complex ecosystems of encoders, switchers, and timing systems running proprietary, stripped-down operating systems. This specialized equipment often lacks the processing power or software architecture to support the security agents, digital certificates, or frequent authentication challenges that are pillars of enterprise zero trust. Forcing such protocols onto these devices would be akin to asking a Formula 1 car to stop at every toll booth—the performance degradation would defeat its purpose. Any security solution that compromises the real-time, low-latency requirements of a live signal is a non-starter, making the standard IT playbook not just impractical, but actively disruptive to the core business of broadcasting. This technological chasm demands a security paradigm built on different principles.

This challenge is compounded by the industry’s ongoing migration away from self-contained, physically secure facilities to highly interconnected, IP-based infrastructures. For decades, broadcast plants operated like secure fortresses, with coaxial SDI cables forming a closed loop where risk was managed primarily through restricted physical access. The transition to IP and cloud-based workflows has completely dissolved this traditional perimeter, creating a vastly expanded and more porous attack surface. As a result, broadcasters now face the same sophisticated threat landscape as any modern enterprise but must defend systems where even a momentary disruption is unacceptable. The old assumption of a trusted internal network is now a critical vulnerability. In this new reality, assuming internal safety is a direct path to disaster, as even a single compromised device could potentially expose an entire network, necessitating a security model that presumes a hostile environment both inside and out.

Redefining Security Through Continuous Behavioral Verification

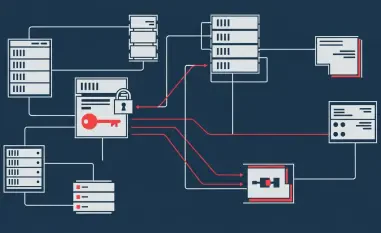

The broadcast-adapted model of zero trust makes a critical pivot from authenticating identity to validating behavior. Rather than repeatedly demanding credentials to confirm who a device is, this approach focuses on continuously monitoring how it is acting. This involves establishing a detailed, pre-defined baseline of normal operational activity for every component in the workflow, including network traffic patterns, expected communication paths, and standard device configurations. The security system then perpetually observes the network, watching for any deviation from these established norms. This method of continuous, non-intrusive verification allows security to be omnipresent without being disruptive, respecting the stringent performance requirements of on-air equipment. It is a fundamental shift from a security posture based on periodic checks to one based on constant, silent oversight of the entire production environment.

This behavior-centric security paradigm is perfectly suited for live production because it functions as a silent guardian, operating entirely in the background without affecting the live signal path. Its value lies in its ability to detect and respond to threats in real time before they can impact the broadcast. For example, if an encoder, which should only be sending its feed to a specific distribution point, suddenly attempts to communicate with an unknown external server, the system would instantly recognize this anomalous behavior. This deviation from the established baseline would trigger an immediate, automated response, such as generating an alert for the network operations team or automatically quarantining the device by blocking its unauthorized traffic. This proactive threat mitigation neutralizes potential security breaches before they can escalate, providing a robust layer of defense that works in harmony with the unforgiving demands of live production.

Evolving Zero Trust for Granular Control and Operational Agility

Forward-thinking solutions are now extending this adapted zero trust concept even deeper into the media workflow, offering more granular and sophisticated layers of control. One advanced implementation moves beyond network-level security to enforce identity at the content level itself. In this model, every user, encoder, and software process must authenticate before a single packet of video or audio can even leave its point of origin. This ensures that identity verification happens “at the packet and pixel level,” creating an unbroken chain of custody for the content. Another powerful evolution utilizes Software-Defined Networking (SDN) to enforce a proactive “allow list” security posture. Unlike traditional “deny lists” which reactively block known threats, an allow list architecture operates on the principle that any network access not explicitly granted is denied by default. This dramatically reduces the potential for unauthorized communication, providing a far more stringent and proactive security framework from the outset.

The ultimate challenge lies in implementing these robust security measures without introducing “security friction” that impedes the fast-paced, collaborative nature of modern production. Workflows increasingly involve remote operators, freelance talent, and third-party vendors, all requiring seamless access to resources. The solution is not to impose cumbersome, blanket restrictions but to build a security framework that combines strong foundational controls—such as multi-factor authentication and well-defined permissions—with dynamic, real-time monitoring. In this context-aware system, security policies are applied intelligently based on a variety of factors, including user behavior, data sensitivity, and the specific production environment. Zero trust in broadcast, therefore, manifests not as incessant login prompts but as constant oversight, automated alerts, and the capacity for rapid isolation when anomalies appear, ensuring security is both powerful and flexible enough for the real world.

A Strategic Shift Toward Operational Resilience

The successful integration of zero trust into live production environments required a fundamental reconceptualization of cybersecurity itself. It was no longer viewed as a siloed IT problem but was instead elevated to a core component of broadcast continuity and operational risk management. This crucial shift in perspective reframed the objective of security from simply protecting data to actively preserving the integrity of live programming and maintaining invaluable audience trust. The industry came to understand that the rigid, identity-centric models of the enterprise world were incompatible with the unique hardware and absolute performance requirements of broadcasting. The adapted model that emerged was one that was inherently non-intrusive, behavior-focused, and relentlessly continuous. It accepted that some legacy devices could not prove their identity in conventional ways and instead focused on a more practical and essential goal: ensuring every component behaved exactly as expected, at all times. Ultimately, this new philosophy was not about trusting nothing; it was about verifying everything—quietly, constantly, and without ever taking the show off the air.