With a deep background in threat intelligence and corporate security, Malik Haidar has spent his career on the front lines, dissecting the anatomy of sophisticated cyberattacks. Today, he joins us to unravel a particularly alarming campaign where a nation-state actor, UNC6201, exploited a hard-coded credential in a widely used Dell product for two years. Our conversation will explore the lifecycle of such a breach, from the initial exploit to long-term persistence, touching on the development oversights that create these vulnerabilities, the critical importance of network segmentation, and how security teams can hunt for these hidden threats.

A nation-state actor, UNC6201, reportedly exploited a hard-coded credential for two years. Could you detail the typical post-exploitation steps in such a campaign? Specifically, how does a novel C# backdoor like Grimbolt help an attacker maintain long-term persistence and evade detection?

Once an actor like UNC6201 gets in using a golden ticket like a hard-coded credential, their first priority is to blend in and make the environment their own. They aren’t just there for a quick smash-and-grab; they’re playing the long game. The initial access, in this case authenticating to the Tomcat Manager, is just the first step. From there, they move to establish persistence that will survive reboots or software updates. This is where a tool like Grimbolt becomes absolutely critical for them. It’s not just some off-the-shelf malware; it’s a novel C# backdoor. The fact that it’s compiled using native ahead-of-time compilation makes it a nightmare for reverse engineers and automated analysis tools, allowing the attackers to operate under the radar for an extended period, in this instance, for two full years. This stealth allows them to quietly move laterally across the network, escalating privileges and exfiltrating data without raising any alarms.

The vulnerability involved default “admin” credentials left in a Tomcat configuration file. Can you explain the development lifecycle failures that allow such an oversight to reach production? Please provide some anecdotes on why these flaws are often missed by internal security testing, especially in legacy codebases.

This is a classic case of technical debt coming back to haunt an organization. During the early development stages of a complex product like this, developers often use hard-coded accounts to make internal components talk to each other. The intention is always to remove them later, but as deadlines loom and codebases grow, these temporary fixes become permanent fixtures. They get forgotten, buried deep within configuration files like the tomcat-users.xml file identified here. Internal security testing often focuses on the shiny, customer-facing parts of an application, like the primary login portals. They’re not always looking at internal admin endpoints like a Tomcat Manager, which might be assumed to be inaccessible from the outside. It’s especially prevalent in older, sprawling codebases where the original developers may be long gone, and the new team is hesitant to touch anything for fear of breaking a critical function.

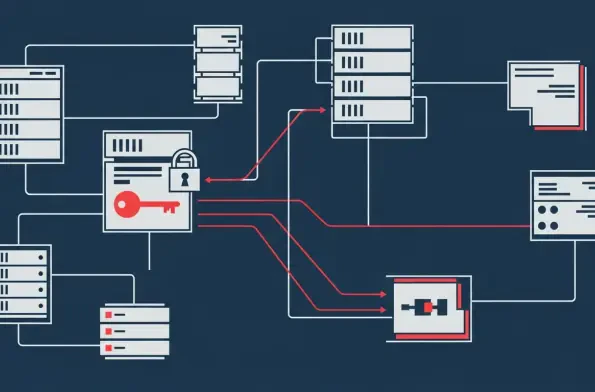

After compromising a data protection appliance, attackers were able to pivot to the VMware virtual infrastructure. What are the primary pathways for this type of lateral movement, and what specific network segmentation strategies could effectively contain an initial breach on an appliance to prevent it from spreading?

Pivoting from an appliance to the core virtual infrastructure is the nightmare scenario for any security team. Once the attackers gained root on the Dell appliance, they essentially owned a trusted system on the network. From that vantage point, they can scan for other vulnerable systems, exploit trust relationships, and steal credentials that are cached in memory. The most common pathway is exploiting shared network access and weak access controls between the management appliance and the hypervisors it controls. To prevent this, strict network segmentation is non-negotiable. The data protection appliance should have been isolated in its own security zone, with firewall rules that only permit the absolute minimum required traffic to the VMware vCenter and ESXi hosts. This is a zero-trust approach; you assume the appliance could be compromised and build defenses to contain it. Micro-segmentation within the virtual environment itself would provide another layer, preventing a compromised virtual machine from communicating with others it has no business talking to.

Attackers used the Apache Tomcat Manager to deploy malicious files. For security teams now looking for similar threats, what specific indicators of compromise or anomalous web requests should they hunt for? Please provide a few examples of logs or alerts that would signify this type of activity.

Security teams should be actively hunting for any web requests to the Apache Tomcat Manager, especially from unexpected IP addresses. An alert should immediately trigger if you see a request to the /manager/text/deploy endpoint, as this is the direct path used to upload a malicious WAR file. You’d want to look for logs showing a successful authentication using the “admin” username followed by a POST request to that deployment endpoint. Another key indicator would be the sudden appearance of new, unexpected web application contexts or suspicious files like JSP webshells in the Tomcat webapps directory. Monitoring command-line activity on the appliance for processes spawned by the Tomcat service is also crucial. Seeing the Tomcat user executing commands like whoami or trying to establish network connections to external systems would be a massive red flag that you’re dealing with an active compromise.

What is your forecast for the prevalence of hard-coded credential vulnerabilities?

I believe we’ll continue to see these vulnerabilities surface, particularly in the Internet of Things (IoT) and Operational Technology (OT) sectors, as well as in older, legacy enterprise software. The pressure to release products quickly often leads to shortcuts, and security hygiene can fall by the wayside. As codebases age and are passed between development teams, the institutional knowledge of why a certain hard-coded account exists is lost, making it more likely to persist into production. While awareness is growing and tools for static code analysis are getting better, the sheer volume of existing legacy code means we’ll be playing catch-up for years. Attackers know this is a fruitful hunting ground, so they will continue to probe for these simple, yet devastating, oversights.