A deeply troubling security advisory has revealed the emergence and explosive growth of a sophisticated malware operation that shatters the foundational assumption of home network security, proving that devices operating behind a standard router are no longer inherently safe from external threats. This malware, identified as the Kimwolf botnet, has already ensnared over two million devices globally, with significant infection clusters in Vietnam, Brazil, India, Saudi Arabia, Russia, and the United States. The compromised systems are coerced into a massive network designed to relay malicious internet traffic, creating a formidable infrastructure for cybercriminals. This botnet facilitates a wide array of illicit activities, ranging from large-scale advertising fraud and aggressive content scraping to systematic account takeover attempts. Furthermore, it possesses the capability to launch powerful distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, potent enough to render major websites and online services inaccessible for extended durations, underscoring the severe and immediate danger it poses to the digital ecosystem.

The Unholy Alliance of Insecure IoT and Proxy Networks

The Primary Targets

The operational success of the Kimwolf botnet is built upon a perilous convergence of two major failings within the consumer electronics and internet services landscape: the unchecked proliferation of insecure Internet of Things (IoT) devices and the illicit exploitation of residential proxy networks. The primary infection vectors and targets are predominantly low-cost, unsanctioned Android TV boxes and a wide array of internet-connected digital photo frames. These devices, frequently marketed under a multitude of no-name or generic brands, are readily available on major e-commerce platforms, including Amazon, Best Buy, Newegg, and Walmart. Their widespread availability and low price point make them attractive to consumers, yet they represent a significant and often overlooked security risk. The very nature of their manufacturing and distribution channels creates a fertile ground for compromise, turning an innocuous-looking media player or picture frame into a potential gateway for malicious actors to infiltrate a private home network.

These budget-friendly electronics become prime targets not just for their technical vulnerabilities but also because of the ecosystem that surrounds them. Many are explicitly marketed with the promise of providing “free” access to premium, subscription-based video content, which is a thinly veiled reference to piracy. This marketing angle attracts a specific consumer demographic that may be less concerned with security best practices and more focused on cost savings. The software required to enable this illicit streaming is often sourced from unofficial, unregulated app stores, which are notorious for hosting malware-laden applications. Consequently, users are often tricked into willingly installing the very software that compromises their devices and integrates them into a botnet. This business model creates a self-perpetuating cycle where the demand for pirated content fuels the distribution of insecure hardware, which in turn feeds the growth of malicious networks like Kimwolf, making the consumer an unwitting accomplice in their own security breach.

Dual-Pronged Vulnerabilities

A substantial number of these unsanctioned IoT products are compromised before they even reach the consumer, shipping directly from the factory with malware pre-installed deep within their operating systems. In scenarios where the device is initially clean, users are frequently compelled to download malicious applications from untrusted sources as a prerequisite for unlocking the device’s advertised functions, particularly the piracy of streaming services. The most prevalent form of this embedded malware is software that silently transforms the device into a residential proxy node. This conversion allows the device’s internet connection and its associated residential IP address to be surreptitiously sold to third parties on the open market. These third parties can then route their own internet traffic through the compromised home network, using it as a cloak for their activities, which can range from benign market research to more sinister operations like spamming, phishing, or launching cyberattacks, all while appearing to originate from an innocent household.

More critically, these devices are constructed on microcomputer boards that are fundamentally insecure by design, lacking basic authentication and security mechanisms that are standard in products from reputable manufacturers. A key vulnerability identified as a primary enabler for the Kimwolf botnet is the default activation of the Android Debug Bridge (ADB) mode. ADB is a powerful and versatile command-line tool intended for developers and manufacturers to diagnose issues, install software, and gain deep administrative access to a device’s operating system. When this “super user” access mode is left active and unprotected on a consumer product, it effectively creates a wide-open backdoor. Any other user or device connected to the same local network can establish a connection to the vulnerable device’s ADB port, typically 5555, using a simple command. This connection requires no password or authentication, granting the attacker complete and unfettered control to install any software, including the Kimwolf botnet malware, without the user’s knowledge or consent.

Anatomy of the Attack

The Propagation Breakthrough

The diabolical innovation behind the Kimwolf botnet lies in its method of propagation, which masterfully combines these inherent device vulnerabilities with a critical weakness in the architecture of residential proxy services. Benjamin Brundage, the 22-year-old founder of the security firm Synthient, was instrumental in uncovering this sophisticated attack mechanism. His investigation revealed that the Kimwolf operators were exploiting a fundamental flaw that allowed them to pivot from a public-facing proxy connection back into the supposedly secure private network of a home. While large residential proxy networks typically implement rules to prevent their customers from accessing the private, internal network address spaces of the proxy endpoints, such as the common 192.168.x.x range, Brundage discovered that the Kimwolf attackers had engineered a clever technique to circumvent these safeguards, turning the proxy service itself into a weapon.

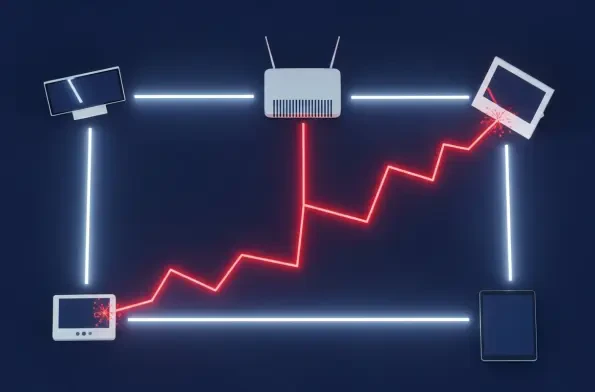

This circumvention was achieved through a manipulation of the Domain Name System (DNS). The attackers registered custom domain names and configured their DNS records to resolve not to a public internet address, but to the private, internal IP addresses they wished to target. By routing their traffic through the proxy service using these malicious domain names, they were able to trick the proxy’s infrastructure into forwarding their malicious traffic past its own security filters and directly onto the local area network (LAN) of an unsuspecting user. This technique effectively created a tunnel from the public internet, through the initial proxy device, and into the trusted internal environment of the home network. This breakthrough allowed the attackers to bypass the primary defense of a router’s firewall, giving them a foothold inside the network from which they could launch further attacks and propagate their malware to other vulnerable devices.

A Step-by-Step Intrusion

The attack sequence is a multi-stage process that begins when a device already infected with residential proxy software connects to a new Wi-Fi network. This initial vector could be a guest’s smartphone running a malicious “free” VPN or gaming app, or even one of the homeowner’s own devices compromised through other means. Once this device connects to the home’s Wi-Fi, it registers itself with its parent proxy service, effectively listing the home’s public IP address for rent on a proxy marketplace. This single action exposes the entire home network to potential targeting by anyone willing to pay for access. The home’s internet connection is now, for all intents and purposes, a commercial product available to anonymous buyers around the world, setting the stage for the subsequent intrusion by the Kimwolf operators.

The Kimwolf operators then purchase access to this newly available proxy endpoint, renting the home’s internet connection for their malicious purposes. They immediately leverage the DNS vulnerability to pivot from the initial proxy device and “tunnel back” onto the home’s private local area network. Once inside this supposedly secure digital sanctuary, their malware begins to actively scan the internal network for other vulnerable systems. The primary targets of this scan are the aforementioned unsanctioned Android TV boxes and digital photo frames that are known to have the ADB port open and unprotected. Upon discovering a target, the malware uses the open ADB port to gain complete administrative control, installs the Kimwolf botnet client, and adds another device to its expanding army. This insidious, automated process allows the botnet to spread laterally from device to device and from home to home with terrifying efficiency.

Unmasking the Culprit and Its History

The IPIDEA Connection

The meticulous investigation led by Brundage and Synthient established a direct and overwhelming correlation between the Kimwolf botnet’s explosive growth and the infrastructure of a single, massive residential proxy provider: the China-based IPIDEA. Synthient’s research, which involved analyzing network traffic and tracking infection patterns, showed a near one-to-one overlap between newly infected Kimwolf nodes and residential proxy IP addresses being offered for rent by IPIDEA. This provider is widely considered to be the world’s largest residential proxy network, boasting a vast pool of IP addresses sourced from devices across the globe. The connection was so strong that in one observed instance, Brundage watched the botnet rebuild itself from a near-zero state to two million infected systems in just a couple of days, a feat accomplished almost exclusively by exploiting devices within IPIDEA’s proxy pool.

Further analysis of the devices operating within the IPIDEA network painted an even grimmer picture. The research revealed that over two-thirds of the systems offered as proxy endpoints by the company were Android devices. A significant portion of these Android systems were found to be vulnerable to compromise without any form of authentication, primarily through the open ADB port vulnerability. This finding suggested that the very business model of IPIDEA was heavily reliant on a foundation of insecure devices, making it an ideal and fertile breeding ground for a botnet like Kimwolf. The sheer scale of IPIDEA’s operation, combined with the systemic insecurity of its device pool, created a perfect storm that enabled the botnet’s operators to expand their network at an unprecedented rate, highlighting the critical role that large-scale proxy providers can play, wittingly or unwittingly, in facilitating global cybercrime.

A Pattern of Deception

In mid-December 2023, armed with incontrovertible evidence, Brundage and Synthient issued a detailed security advisory to IPIDEA and ten other affiliated proxy providers, outlining the critical vulnerability and its exploitation by the Kimwolf botnet. The initial response from IPIDEA was denial, with the company publicly refuting any association with botnet activity. However, behind the scenes, IPIDEA’s security officer eventually acknowledged the issue in communications with Brundage. The company’s official explanation was that the vulnerability was traced to a “legacy module used solely for testing and debugging purposes” that had been mistakenly left active. They subsequently confirmed that they had implemented fixes, which included blocking access to internal network spaces, instituting stricter DNS resolution controls, and blocking traffic on high-risk ports to prevent lateral movement within customer networks.

This incident is not an isolated case but rather part of a larger, persistent trend. There is a strong consensus among security experts, including Riley Kilmer of Spur.us, that IPIDEA is a reincarnation of the notorious 911S5 Proxy network. The 911S5 service, which was immensely popular within cybercrime circles for its reliability and scale, abruptly shut down its operations in 2022 following extensive investigative reporting that exposed its connections to widespread fraud and malware distribution. The historical context suggests a recurring pattern where malicious proxy services, upon being exposed, simply shut down and rebrand under a new name to evade scrutiny from law enforcement and security researchers, all while continuing their illicit operations. This chameleon-like behavior makes it incredibly difficult to permanently dismantle these criminal enterprises, as they continue to exploit the same fundamental security weaknesses in the consumer electronics market.

A New Paradigm for Home Security

The practical implications of these findings were deeply concerning, as they effectively rendered the traditional security model of a “safe” internal network obsolete. The long-standing belief that a firewall-protected LAN was a trusted environment was shattered by the demonstration that a single compromised device could serve as a bridgehead for attackers. The presence of an infected smartphone belonging to a guest, or even a homeowner’s own compromised device, could allow malicious actors to infiltrate and systematically compromise other vulnerable systems within the network. This reality expanded the threat beyond simple botnet infections, opening the door to more severe attacks. For instance, an attacker with internal access could potentially modify a router’s DNS settings, redirecting all web traffic from every device in the home through malicious servers to steal credentials and financial information, a technique reminiscent of the widespread DNSChanger malware campaigns of the past. It became clear that network hygiene and device scrutiny were no longer optional but essential practices for modern digital life.